Food In Studio Ghibli Movies

Known as "the Walt Disney of Japan" and widely considered the greatest animator of our time, Hayao Miyazaki is beloved worldwide. This includes the United States, where English-dubbed and subtitled versions of his movies are screening at select theaters across the country as part of Studio Ghibli Fest, an annual celebration of the prolific filmmaker's output.

Among the many recurring themes that are central to the plots of his work, including 1988's My Neighbor Totoro and the 2001 Academy Award-winning Spirited Away, one trope in particular continues to generate endless fan appreciation: his obsession with food. Miyazaki-focused Tumblr accounts, meal recreations, listicles, travel guides, and how-tos all serve to honor the director's love of eating and cooking, and a clip of Miyazaki himself making Poor Man's Salt Flavored Ramen for his burnt-out crew on deadline has amassed more than a million views.

Miyazaki -- who recently came out of retirement to finish yet another project -- is revered as one of the pillars of foodie film, from the Euro-focused meals of The Castle of Cagliostro and Porco Rosso to the Asian food feasts served at Yubaba's sentō (or bathhouse) for spirits in Spirited Away. His food scenes resonate because they're beautifully drawn and are deeply connected to the characters. But there's another layer to why they're important, and it's tied to Japanese food traditions.

"Drawing food is drawing culture and history," reads the description of Delicious! Animating Memorable Meals, an exhibit at Tokyo's Ghibli Museum curated by Hayao Miyazaki's son Gorō that pays homage to all the carefully illustrated cuisine in his father's work. But to talk about the essentialness of food to Miyazaki's films in these terms, we need to understand washoku. Literally translating to "food harmony," it's a traditional Japanese cuisine with a long and rich history.

"The simplest definition of washoku I can give is that it is the indigenous food culture of Japan," says Elizabeth Andoh, a graduate of the Yanagihara School of classical cuisine in Tokyo, contributor toThe New York Times and Gourmet before it shuttered, and founder of culinary arts program A Taste of Culture. Andoh wrote her cookbook Washoku in 2005, more than eight years before the cuisine was named to UNESCO's Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. She says the title choice baffled her peers in Japan. "They said, 'You don't call a book Washoku,'" she recalls. "'That's just what everybody eats!'"

However, there are plenty of food preparations that fall outside the tradition of washoku, Andoh clarifies. She cites nihon ryori, meaning "Japanese food," which typically refers to restaurant-prepared food. Yōshoku, or Japanese cuisine inspired by European and American cooking, includes a number of popular dishes like omuraisu (rice omelettes), karēraisu (curry rice), and korokke (fried croquettes). On the opposite end of the culinary spectrum is kaiseki, Japan's highest form of intricate cooking in a multi-course fine dining experience.

The history of washoku dovetailed with Japan's geography and history, explains Tadashi Ono, a Tokyo-born cookbook author and chef who has opened multiple Japanese restaurants in Brooklyn. "The traditional or old Japanese eating style is very simple and minimal because the mountainy soil of Japan used to be very poor," he says. "For instance, it's got influence from Buddhist food [in] that the amount of food is very minimal. When people are not satisfied [with] the amount of food, they try to get satisfied from the beauty [of it] to fill the spirit and mind."

The okayu, or rice porridge, from Princess Mononoke is especially exemplary of this simplicity. "It was traditionally eaten by monks for breakfast in temple," Ono says. The dish itself is a staple in East Asian cultures -- there's congee in China, jook in Korea. (Jook, it should be noted, appears near the end of the second season of Avatar: The Last Airbender, an American cartoon with heavy Miyazaki influences.) The big difference between okayu and its cousins is that the Japanese don't flavor okayu, Ono says, opting instead to add in side-dishes and condiments after cooking. "It's easy to digest in early morning and gives you quick energy," added Ono. "We eat okayu when we get sick."

Minimizing food waste is also a core tenet of washoku cooking, Ono says. "We developed recipes and dishes [that] use every part of ingredients. Skin, roots, leaves and everything." But washoku is more than just the food itself and its preparatory techniques -- it extends to an entire mindset, "a philosophy about food and the meaning of food in the larger context of living," says Andoh. "There are some very specific guidelines for putting together a meal," called goshiki gomi gohō -- five colors, five flavors, five ways, in that order. "And if you are attentive to these things, you're automatically going to create a meal that is harmonious, satisfying, nourishing, and all the rest of it."

The washoku ethos certainly finds its way into Miyazaki's films, often in small ways -- from the foods prepared, to the ways they are prepared, to the context in which the cooking happens. A close reading of a scene from My Neighbor Totoro shows that even one of Ghibli's most child-friendly films is exceptionally attentive to washoku in everyday Japanese life. In it, Satsuki, the elder Kusakabe sister, prepares bento boxes for her family. The details in the bento reinforce tradition, according to Andoh: the okama for cooking rice, the shamoji (the paddle) sticking out from that lid, the foamy rice water boiling over. Placing the umeboshi, or pickled plum (a good source of vitamin C, says Ono), in the center of the rice is referred to as hino maru, a callback to the national flag of Japan. This styling is often used in "very down home, old-fashioned, Grandma-used-to-make-it kind of food," says Andoh. "Looking at that picture, I immediately have a picture of -- if not a farmhouse, at least it's not a very urban setting. This is very classic mid-1960s." Since Totoro takes place in postwar rural Japan, this depiction is right on target.

In Castle in the Sky, the nimono -- literally meaning "the simmered thing," it's generally made up of a base ingredient simmered in a flavored stock -- encapsulates the "most fundamental cooking in Japanese cuisine," says Ono. "We traditionally cook the nimono in one pot over a fire [in a] hearth in the country house. People surround the hearth and eat it from the pot in the center." The pot the nimono is cooked in packs meaning, too: its size, Andoh notes, is consistent with traditionally-made takidashi -- food cooked en masse in the wake of a natural disaster, although it can also refer batches made or for large gatherings.

The onigiri given to Chihiro in Spirited Away is yet another item pared down to its simplest form: just a ball of rice. Wrapped in takēnokawa, dried bamboo leaves, they're "an old-fashioned Showa-era image," Andoh says.

"All of these things are ordinary in the sense that they are extremely indicative of Japanese food culture and Japanese culture in general," Andoh continues. As the Ghibli Museum puts it: "The foods that appear are not particularly special, appearing in our lives quite commonly. But their appearance in the films always has special meaning." Since attention to detail and realism treated incidentally is one of Miyazaki's greatest strengths, this isn't much of a surprise.

"Cuisine has the biggest role in the life of Japanese," Ono says. "We say 'live to eat,' not 'eat to live.'" This is honored -- or at least referred to -- in Japanese art and pop culture everywhere, much of which is food-focused. On-screen, that includes classic films like Tampopo and Jiro Dreams of Sushi and contemporary live-action TV shows like Samurai Gourmet and Midnight Diner: Tokyo Stories. In the animated realm, beloved series like Cowboy Bebop and Samurai Champloo take great pains to illustrate the food eaten -- or, more often, lusted over -- by the down-on-their-luck protagonists, both in the space-age future and in Japan's Edo period.

Another anime staple One Piece features a gourmet chef, the pirate "Black Leg" Sanji, as one of its central characters. The highly-rated, currently-running Shokugeki no Soma follows young chefs coming up in a competitive Japanese culinary academy where exquisitely-cooked meals elicit physically prurient reactions. The number of examples of drawn food in anime goes on and on.

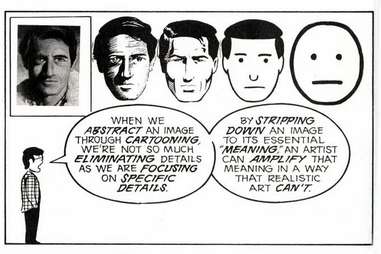

The cartoonist Scott McCloud digs into why these instances of illustrated meals resonate so deeply with viewers (albeit in a different context) in his most famous work of graphic nonfiction, Understanding Comics. McCloud puts forth a theory of iconography that argues, in effect, that readers of comics have an easier time identifying emotionally with the text's characters than with real people -- or characters performed by them -- because cartoon features can be drawn to be less specific, thus making them more universal.

"The more cartoony a face is, for instance, the more people it could be says to describe," McCloud writes. "When we abstract an image through cartooning, we're not so much eliminating details as we are focusing on specific details. By stripping down an image to its essential 'meaning,' an artist can amplify that meaning in a way that realistic art can't."

Ditto food in cartoons. Because they don't have to look necessarily photorealistic, drawings of food can more easily inhabit our ideals of what food should look like. The portrayals of food in Miyazaki's films perform this feat perfectly -- just think of how your mouth watered the first time you saw Chihiro's parents give in to the allure of the buffets prepared for the spirits in Spirited Away, or how the steaming bowls of ramen in Ponyo made you crave a serving of your own.

"Food that is still warm, that looks soft and tender, with the wonderful flavor showing on the faces of those eating them -- these scenes of meals are appealing and charming," the Ghibli Museum's exhibit description reads. At their core, Miyazaki's films exude a sense of magic and wonder; so of course, every scene would serve this mission, especially when it comes to the role of food in the communal experiences of celebration and consolation. Even at its most ordinary, food provides something important to livelihood, beyond sustenance. "Food can be drawn to appear even more delectable than the real thing," writes the Ghibli Museum, "creating scenes of joy."

Sign up here for our daily Thrillist email and subscribe here for our YouTube channel to get your fix of the best in food/drink/fun.

John Maher is a writer and editor in New York. He co-runs the animation blog The Dot and Line. Follow him on Twitter @JohnHMaher.

Food In Studio Ghibli Movies

Source: https://www.thrillist.com/entertainment/nation/hayao-miyazaki-movies-animated-food-porn

Posted by: wilsonexte1947.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Food In Studio Ghibli Movies"

Post a Comment